By Chris Perkins, writer and editor, GM News

By Chris Perkins, writer and editor, GM News

HERO IMAGE:

HERO CAPTION:

COPY:

As the Director of Robotics Strategy at GM’s Autonomous Robotics Center (ARC), Mikell Taylor is helping develop the mobile robots that are designed to make automotive production safer for factory workers and more efficient. As a mother, she’s helping develop the roboticists of the future as coach for her daughter’s FIRST LEGO League robotics team.

Developing next-generation mobile robots for GM’s automotive factories is quite a different task from building LEGO robots. But there is some surprising overlap.

“The thing about the LEGO robotics competition is, you have to make your robot move autonomously through this field, which is a hard thing to do,” Taylor explains. “You have to use sensors and timing, figure out how to navigate, figure out what sort of logic you’re supposed to use.”

Her daughter’s team successfully got their LEGO robot navigating through obstacle courses, but they can’t score points from that alone.

“We have to make the robot do things. It has to hit a lever and lift things,” Taylor recalls the kids saying. “That’s a different problem.”

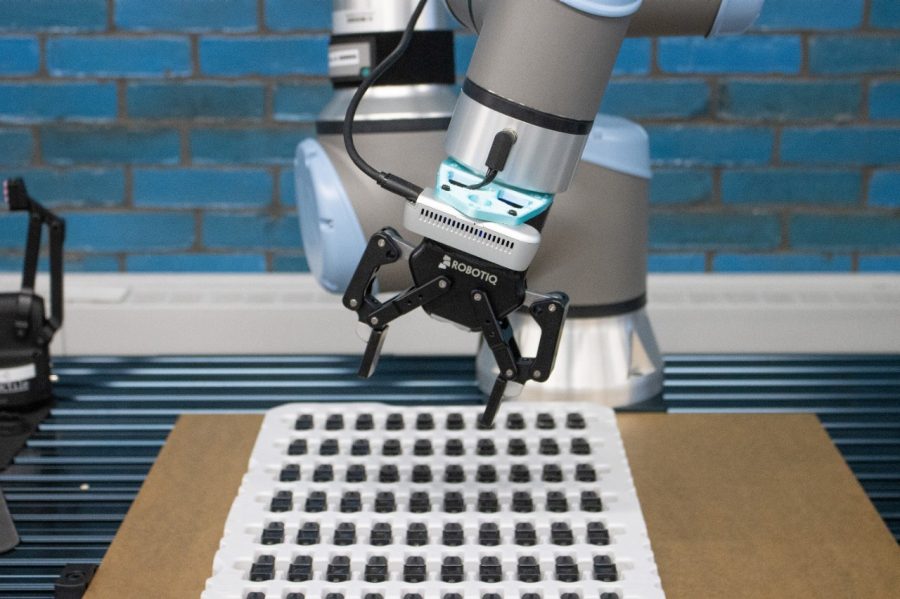

[Image Placeholder]

It’s the same sort of challenge engineers face at the ARC. It’s one thing to create a robot that can safely move around autonomously inside a GM factory; it’s another matter entirely to make that robot add real value by handling repetitive tasks so workers can focus on skilled operations that require human judgment and expertise.

“That’s a lesson here at ARC I’m really pushing: we have the robot running around, but then what it does it do?” Taylor says. “Everyone says, but that’s a different kind of engineering, and I say, ‘yeah, but that’s where the value comes from.’ Having the same conversation with this group of tweens really stood out.”

Taylor’s colleagues at the ARC didn’t take offense to being compared to a group of pre-teens. They found it funny.

Whether it’s at ARC or with her daughter’s FIRST LEGO team, “I think it shows that these are real lessons for any new robotics organization,” Taylor says. “You can try to imitate the success of what others have done, but there are certain things you have to viscerally understand by going through them and having the realization for yourself.”

Like automotive engineering, robotics requires people from many different disciplines in both software and hardware to come together to build a product, but the complexity and the big technical challenges are a little unique in robotics. On top of all that, developing robots to operate in an automotive production environment is uniquely complex – the scale, precision, pace and complexity of the environment are all key considerations.

[Image Placeholder]

“One of the things I love about being part of this team is that our customer is the manufacturing plant teams,” Taylor says. “That’s very different from where I’ve been before. They have very high expectations of what ‘good enough’ is.”

It's a matter of safety, both for those working in the plants and for the vehicles that roll off the assembly line. “It drives us toward this paradigm of true collaborative robotic systems,” she says. “Robots take on physically demanding tasks, reducing safety risks and improving ergonomics for line workers, handling tasks like heavy lifting and repetitive motions, but they're not able to do everything a person can do. And commitment to quality for our customers means eighty percent success from an automation system is not good enough – it may work in some other industries, but it doesn't work here. We need people and robots to be working together.”

There are limits to what you can do with robots. “I think that as roboticists, we have to be incredibly candid with ourselves about what robots can and can't do, and they can't do everything,” Taylor says. The robots the ARC is developing are designed to improve safety, quality, and the ergonomics of car assembly, but there’s no replacing humans.

[Image Placeholder]

“We need human brains and hands and eyes, the expertise our production workers bring – their craftsmanship, problem-solving abilities, their quality eye, and their adaptability. There's no getting around that,” Taylor says.

Robotics expertise goes far beyond the assembly plant at General Motors. The logic powering the sensing systems in assembly robots is very similar to the machine vision that enables GM’s Super Cruise – which will expand to offer eyes-off driver assistance in the 2028 Escalade IQ, beginning with highways1. Naturally, a lot of the engineers on Taylor’s team came with experience in autonomous vehicle development.

And thanks to her robotics coaching, she’s got a great pipeline for future talent.

1 Availability and permissible use may vary by state.

As the Director of Robotics Strategy at GM’s Autonomous Robotics Center (ARC), Mikell Taylor is helping develop the mobile robots that are designed to make automotive production safer for factory workers and more efficient. As a mother, she’s helping develop the roboticists of the future as coach for her daughter’s FIRST LEGO League robotics team.

Developing next-generation mobile robots for GM’s automotive factories is quite a different task from building LEGO robots. But there is some surprising overlap.

“The thing about the LEGO robotics competition is, you have to make your robot move autonomously through this field, which is a hard thing to do,” Taylor explains. “You have to use sensors and timing, figure out how to navigate, figure out what sort of logic you’re supposed to use.”

Her daughter’s team successfully got their LEGO robot navigating through obstacle courses, but they can’t score points from that alone.

“We have to make the robot do things. It has to hit a lever and lift things,” Taylor recalls the kids saying. “That’s a different problem.”

It’s the same sort of challenge engineers face at the ARC. It’s one thing to create a robot that can safely move around autonomously inside a GM factory; it’s another matter entirely to make that robot add real value by handling repetitive tasks so workers can focus on skilled operations that require human judgment and expertise.

“That’s a lesson here at ARC I’m really pushing: we have the robot running around, but then what it does it do?” Taylor says. “Everyone says, but that’s a different kind of engineering, and I say, ‘yeah, but that’s where the value comes from.’ Having the same conversation with this group of tweens really stood out.”

Taylor’s colleagues at the ARC didn’t take offense to being compared to a group of pre-teens. They found it funny.

Whether it’s at ARC or with her daughter’s FIRST LEGO team, “I think it shows that these are real lessons for any new robotics organization,” Taylor says. “You can try to imitate the success of what others have done, but there are certain things you have to viscerally understand by going through them and having the realization for yourself.”

Like automotive engineering, robotics requires people from many different disciplines in both software and hardware to come together to build a product, but the complexity and the big technical challenges are a little unique in robotics. On top of all that, developing robots to operate in an automotive production environment is uniquely complex – the scale, precision, pace and complexity of the environment are all key considerations.

“One of the things I love about being part of this team is that our customer is the manufacturing plant teams,” Taylor says. “That’s very different from where I’ve been before. They have very high expectations of what ‘good enough’ is.”

It's a matter of safety, both for those working in the plants and for the vehicles that roll off the assembly line. “It drives us toward this paradigm of true collaborative robotic systems,” she says. “Robots take on physically demanding tasks, reducing safety risks and improving ergonomics for line workers, handling tasks like heavy lifting and repetitive motions, but they're not able to do everything a person can do. And commitment to quality for our customers means eighty percent success from an automation system is not good enough – it may work in some other industries, but it doesn't work here. We need people and robots to be working together.”

There are limits to what you can do with robots. “I think that as roboticists, we have to be incredibly candid with ourselves about what robots can and can't do, and they can't do everything,” Taylor says. The robots the ARC is developing are designed to improve safety, quality, and the ergonomics of car assembly, but there’s no replacing humans.

“We need human brains and hands and eyes, the expertise our production workers bring – their craftsmanship, problem-solving abilities, their quality eye, and their adaptability. There's no getting around that,” Taylor says.

Robotics expertise goes far beyond the assembly plant at General Motors. The logic powering the sensing systems in assembly robots is very similar to the machine vision that enables GM’s Super Cruise – which will expand to offer eyes-off driver assistance in the 2028 Escalade IQ, beginning with highways1. Naturally, a lot of the engineers on Taylor’s team came with experience in autonomous vehicle development.

And thanks to her robotics coaching, she’s got a great pipeline for future talent.

1Availability and permissible use may vary by state.