By Bob Sorokanich, senior editor, GM News

It’s amazing what you can find in a barn.

In 2024, Josh Quick went to a farm estate sale in the small town of Conesus, about 45 minutes south of Rochester, New York, on the hunt for antique tractor parts. He thought he’d hit the jackpot. “I asked the guy, what do you want for all this stuff? He said, ‘two cases of Busch Light beer,’” Quick told GM News.

Among the pile of parts, Quick found something unusual – a binder full of old pencil-on-paper car drawings.

“I flipped it open, saw the first picture, and thought, that’s cool,” he said. The guy running the estate sale had never seen the binder before. He told Quick to take it. “I just threw it in with the rest of the stuff,” Quick said. “I didn’t know what it was. I left it on the seat of my truck for three or four days. I was more excited about the tractor stuff.”

Soon, curiosity took over. Quick flipped through the collection of hand-drawn automobiles, nearly 80 pages preserved in plastic sleeves. The images, all dated from the summer of 1940, show visions of what General Motors vehicles – Buicks, specifically – might look like in the far-off future of 1942.

Quick is a lifelong gearhead. He has a popular YouTube channel, Quick Speed Shop, where he documents his work restoring vintage cars and trucks and building wild hot-rods. He’s extremely knowledgeable on automotive history, and as he flipped through the pages of his barn-find binder, he began recognizing some of the names signed to the artwork. “That’s when I put the pieces together,” he said.

The cars depicted in this binder were never put into production, but the artists who drew them went on to become some of the most influential figures in American car design. This collection, forgotten for decades in a New York State barn, was a missing piece of history from the Detroit Institute of Automobile Styling, a General Motors-operated school that launched the careers of some of the greatest car designers in history.

The Detroit Institute of Automobile Styling was, like so many aspects of the car-design industry, a brainchild of Harley Earl. Born in California in 1893, and largely self-taught, Earl spent his early career designing custom bodywork for the luxury cars of Hollywood movie stars. He was hired by General Motors in 1927, where he established the Art & Colour Section (spelled the British way for added panache).

In the late 1920s, most mainstream car companies approached styling as an afterthought. With Art & Colour, GM became the first automotive manufacturer to standardize the automotive design process in product development. But staffing this department proved challenging for Earl.

“He was looking for designers, but he had to train them as well, because there were no schools at the time that had a curriculum in automotive or transportation design,” said Christo Datini, manager of the GM Design Archive & Special Collections. In 1938, Earl launched the Detroit Institute of Automotive Styling. Operated by GM, the school served two purposes: Training the next generation of car designers, and recruiting the best to come work at GM.

Initially offered as an in-person classroom course, the DIAS shifted to a correspondence model after World War II. Period advertisements boast of a curriculum “scientifically planned and packed with clear concise inside information on techniques and tricks of the trade” – taught by “our staff of top-notch designers” and overseen by Harley Earl himself, already an auto industry legend.

With the Detroit Institute of Automotive Styling, “General Motors Design became a training ground for young designers,” Datini said. At the end of the year-long course, a promising student could even receive an offer to work under Earl. “So many pioneers of design came through GM,” Datini said.

The barn-find binder shows future design legends at the dawn of their careers. Some rose to prominence as leaders at General Motors: Ned Nickles, who styled the groundbreaking 1963 Buick Riviera; Ed Glowacke, who led Cadillac design during its trend-setting 1950s tail-fin era; Clare MacKichan, directly responsible for Chevrolet’s iconic ’55, ’56 and ’57 sedans, not to mention the first generation of Corvettes.

DIAS had influence far beyond General Motors. Included in Quick’s binder were sketches by Joe Oros, credited with designing the first Ford Mustang; Gene Bordinat, who later served as a vice president at Ford; and Elwood Engel, later a vice president at Chrysler. “The guys in that binder designed every single important car in Detroit from 1952 to 1974,” Quick said.

The collected works seems to come from a single semester of classwork at DIAS, April through August, 1940. They appear to stem from a single exercise: Proposing designs for model-year 1942 Buicks. Flipping through the pages, you can see the work becoming more advanced. Straightforward, blueprint-style views evolve into fanciful illustrations of gleaming speedsters dripping with chrome. Occasionally, a speeding airplane or futuristic monorail train soars across the background, symbolizing a thoroughly modern age of transportation.

Some of these automotive daydreams have a realistic bent, with toothy grilles and Art Deco frills that would fit right in on any American street in the early 1940s. Others are fearlessly futuristic, fit for a comic-book crimefighter.

“They’re incredible sketches,” Datini said. “I love the little nuances, when there’s a little bit of added flair.”

No one has figured out how this collection of drawings journeyed from a Detroit classroom to a barn in the Finger Lakes. According to family members, the deceased farm owner was a major car enthusiast, but had no apparent ties to the Detroit auto industry some 300 miles away. The binder itself offers no clues: It bears the name of a defunct GM division that built buses and commercial trucks.

Adding to the mystery, the drawings are in nearly perfect condition – despite their highly unconventional storage. “When we first saw them, I thought they were copies,” Datini said. “They’re relatively delicate, but they’ve survived quite a journey over the past 80 years.”

When Quick realized the historical significance of these drawings, he contacted GM. He brought the binder to the GM design headquarters in Warren, Michigan, where he and Datini thoroughly examined the contents. Eventually, GM acquired the full collection. Each page has been digitized, and the originals are now stored at GM Design, reunited with other archival items from Harley Earl and DIAS.

For Datini, the lost-and-found drawings help illustrate GM’s role in creating the car-design industry as we know it today. “General Motors Design has always been a training ground,” he said. “All of these pioneering designers flowed through GM. You can follow that story from 1927 all the way up to today, with our Outreach and Development programs training the next generation of designers.”

Like everyone else involved in returning these artifacts to GM, Quick is still a bit mystified by how they survived.

“The funny part is, every single thing in that barn was destroyed by mice and squirrels and stuff,” he said. “They ate everything else, but they didn’t eat that book.”

It’s amazing what you can find in a barn.

In 2024, Josh Quick went to a farm estate sale in the small town of Conesus, about 45 minutes south of Rochester, New York, on the hunt for antique tractor parts. He thought he’d hit the jackpot. “I asked the guy, what do you want for all this stuff? He said, ‘two cases of Busch Light beer,’” Quick told GM News.

Among the pile of parts, Quick found something unusual – a binder full of old pencil-on-paper car drawings.

“I flipped it open, saw the first picture, and thought, that’s cool,” he said. The guy running the estate sale had never seen the binder before. He told Quick to take it. “I just threw it in with the rest of the stuff,” Quick said. “I didn’t know what it was. I left it on the seat of my truck for three or four days. I was more excited about the tractor stuff.”

Soon, curiosity took over. Quick flipped through the collection of hand-drawn automobiles, nearly 80 pages preserved in plastic sleeves. The images, all dated from the summer of 1940, show visions of what General Motors vehicles – Buicks, specifically – might look like in the far-off future of 1942.

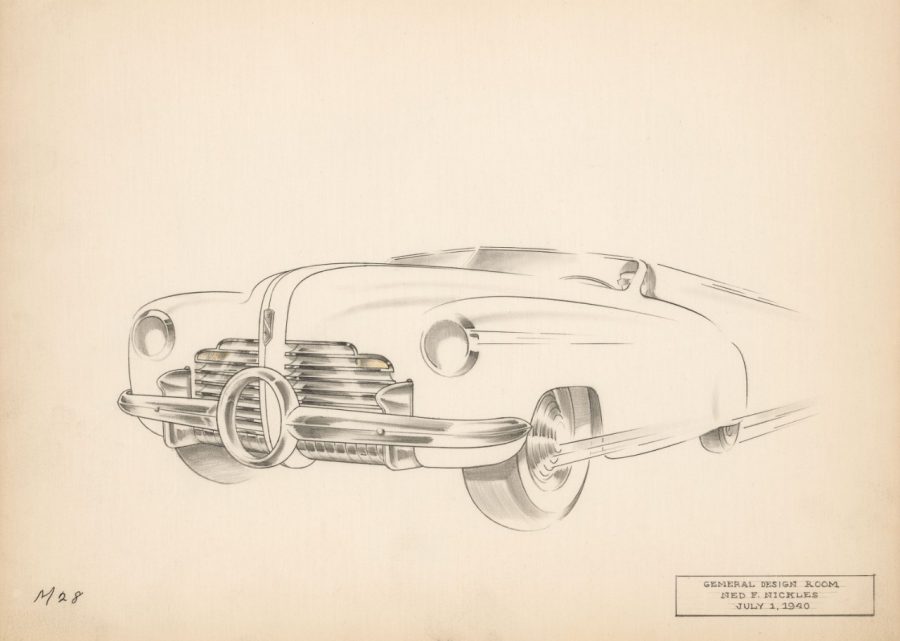

Sketches by Ned Nickles, who went on to become an influential designer at Buick.

Quick is a lifelong gearhead. He has a popular YouTube channel, Quick Speed Shop, where he documents his work restoring vintage cars and trucks and building wild hot-rods. He’s extremely knowledgeable on automotive history, and as he flipped through the pages of his barn-find binder, he began recognizing some of the names signed to the artwork. “That’s when I put the pieces together,” he said.

The cars depicted in this binder were never put into production, but the artists who drew them went on to become some of the most influential figures in American car design. This collection, forgotten for decades in a New York State barn, was a missing piece of history from the Detroit Institute of Automobile Styling, a General Motors-operated school that launched the careers of some of the greatest car designers in history.

Sketches by Ed Glowacke, who led Cadillac design in the 1950s.

The Detroit Institute of Automobile Styling was, like so many aspects of the car-design industry, a brainchild of Harley Earl. Born in California in 1893, and largely self-taught, Earl spent his early career designing custom bodywork for the luxury cars of Hollywood movie stars. He was hired by General Motors in 1927, where he established the Art & Colour Section (spelled the British way for added panache).

In the late 1920s, most mainstream car companies approached styling as an afterthought. With Art & Colour, GM became the first automotive manufacturer to standardize the automotive design process in product development. But staffing this department proved challenging for Earl.

“He was looking for designers, but he had to train them as well, because there were no schools at the time that had a curriculum in automotive or transportation design,” said Christo Datini, manager of the GM Design Archive & Special Collections. In 1938, Earl launched the Detroit Institute of Automotive Styling. Operated by GM, the school served two purposes: Training the next generation of car designers, and recruiting the best to come work at GM.

Drawings by Gene Bordinat, who joined Ford and became an executive.

Initially offered as an in-person classroom course, the DIAS shifted to a correspondence model after World War II. Period advertisements boast of a curriculum “scientifically planned and packed with clear concise inside information on techniques and tricks of the trade” – taught by “our staff of top-notch designers” and overseen by Harley Earl himself, already an auto industry legend.

With the Detroit Institute of Automotive Styling, “General Motors Design became a training ground for young designers,” Datini said. At the end of the year-long course, a promising student could even receive an offer to work under Earl. “So many pioneers of design came through GM,” Datini said.

The barn-find binder shows future design legends at the dawn of their careers. Some rose to prominence as leaders at General Motors: Ned Nickles, who styled the groundbreaking 1963 Buick Riviera; Ed Glowacke, who led Cadillac design during its trend-setting 1950s tail-fin era; Clare MacKichan, directly responsible for Chevrolet’s iconic ’55, ’56 and ’57 sedans, not to mention the first generation of Corvettes.

Sketches by Elwood Engel, who later became an executive at Chrysler.

DIAS had influence far beyond General Motors. Included in Quick’s binder were sketches by Joe Oros, credited with designing the first Ford Mustang; Gene Bordinat, who later served as a vice president at Ford; and Elwood Engel, later a vice president at Chrysler. “The guys in that binder designed every single important car in Detroit from 1952 to 1974,” Quick said.

The collected works seems to come from a single semester of classwork at DIAS, April through August, 1940. They appear to stem from a single exercise: Proposing designs for model-year 1942 Buicks. Flipping through the pages, you can see the work becoming more advanced. Straightforward, blueprint-style views evolve into fanciful illustrations of gleaming speedsters dripping with chrome. Occasionally, a speeding airplane or futuristic monorail train soars across the background, symbolizing a thoroughly modern age of transportation.

Some of these automotive daydreams have a realistic bent, with toothy grilles and Art Deco frills that would fit right in on any American street in the early 1940s. Others are fearlessly futuristic, fit for a comic-book crimefighter.

“They’re incredible sketches,” Datini said. “I love the little nuances, when there’s a little bit of added flair.”

Drawings by Joe Oros, who went on to a design career at Ford.

No one has figured out how this collection of drawings journeyed from a Detroit classroom to a barn in the Finger Lakes. According to family members, the deceased farm owner was a major car enthusiast, but had no apparent ties to the Detroit auto industry some 300 miles away. The binder itself offers no clues: It bears the name of a defunct GM division that built buses and commercial trucks.

Adding to the mystery, the drawings are in nearly perfect condition – despite their highly unconventional storage. “When we first saw them, I thought they were copies,” Datini said. “They’re relatively delicate, but they’ve survived quite a journey over the past 80 years.”

When Quick realized the historical significance of these drawings, he contacted GM. He brought the binder to the GM design headquarters in Warren, Michigan, where he and Datini thoroughly examined the contents. Eventually, GM acquired the full collection. Each page has been digitized, and the originals are now stored at GM Design, reunited with other archival items from Harley Earl and DIAS.

For Datini, the lost-and-found drawings help illustrate GM’s role in creating the car-design industry as we know it today. “General Motors Design has always been a training ground,” he said. “All of these pioneering designers flowed through GM. You can follow that story from 1927 all the way up to today, with our Outreach and Development programs training the next generation of designers.”

Like everyone else involved in returning these artifacts to GM, Quick is still a bit mystified by how they survived.

“The funny part is, every single thing in that barn was destroyed by mice and squirrels and stuff,” he said. “They ate everything else, but they didn’t eat that book.”

Bob Sorokanich is a former automotive journalist whose work has appeared in Road & Track, Car and Driver, Wired, Robb Report, and many other publications. He is senior editor at GM News. Reach him at news@gm.com